Links

- Google News

- Can you Digg it?

- Free Mixtapes

- Bite the Apple

- Search for the Truth

- Kyle Varner

- Losting

- NextGen

- MySpleen

- Cyan Worlds

- whispers in the loggia

- Music Thing

- Triple Helix

- Library

- Blogs for Science!

- Fanta Se

- Adario Strange

- PostSecret

- Cdurkee

- intent

- Mayer Spivack

- FARG

- out of ur

- ice cream dreams

- TMS

- Hello K-47

- Steve Truett

- Gruntose

- Love of Liberty

- I Live on Clay St.

- Torvalds

- Education&Liberty

- Dipset Haiku

danbroussard

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

Freshman Essay

What does it take to get some satisfaction around here?

By Daniel Webster Broussard

Do you desire anything at the moment? Are you thirsty? Perhaps there's a knot in your shoulder that's just in insufferable need of a massage. Have you been reading a fictional story that you just can't wait to conclude? Maybe someone proposed a paradox of thought you can't dismiss, that's been just eating away at your attention. What do you desire?

If you're an animal the answer seems somewhat simple. You desire survival. You forage or hunt for food; you sleep when you're safe, and fight if threatened. Before you die you try to mate at least once, for the sake of the survival of the species, but in short you spend your time surviving.

If you were a god the answer would be a bit more elusive. At a minimum the gods are immortal. They are outside the bounds of a base corporeal decaying existence. Time would not seem to apply to the gods or they are bound by a time that is something well beyond and entirely separate from the time we experience; comparable to ours only as a Euclidean point could be compared to a solid with 3 dimensions. The entirety of Earths history might be some infinitesimally constituent part of god history, but as long as the gods remain defined by immortality facets of their existence, like desire, will remain as foreign to our understanding as that undying nature.

So that leaves the human being torn between the two extremes. We still require maintenance to survive like animals, and mating is beneficial, yet we also seem to posses an undying well of desire to draw on. We don't just have needs we have wants. We are uniquely like gods with higher desire yet trapped in an animal body. Our existence encompasses two experiences, that of the physical visible body, and that of the invisible inner-workings of the intellect. So where should humans seek satisfaction of desire the visible or non-visible worlds?

Before addressing the end to desire let's focus some effort on a better understanding of this dual human experience. In the latter half of the sixth book of Plato's Republic Socrates and Glaucon's discussion addresses this very idea. They establish an understanding that the sun is the most important and most representative of the good of the elements in the visible world, and that its position is in proportion with an all-encompassing good presiding over the non-visible. At line 508c Socrates says,

“This, then, you must understand that I meant by the offspring of the good which the good begot to stand in a proportion with itself: as the good is in the intelligible region to reason and the objects of reason, so is this [The Sun] in the visible world to vision and the objects of vision.”

He expounds further on this comparison in 509b saying,

“The sun, I presume you will say, not only furnishes to visibles the power of visibility but it also provides for their generation and growth and nurture though it is not itself generation...”

“...In like manner, then, you are to say that the objects of knowledge not only receive from the presence of the good their being known, but their very existence and essence is derived to them from it, though the good itself is not essence but still transcends essence in dignity and surpassing power.”

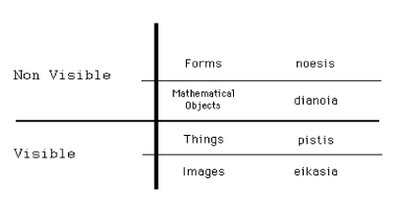

After Glaucon assures Socrates he has a comprehension of these two types, the visible and the intelligible, Socrates is finally in the position to introduce his most advanced metaphorical tool. He tells Glaucon to imagine a line cut first into unequal parts and then to cut each of those parts in the same ratio as the first cut. In doing so he should label a part from the first cut as visible and the other as intelligible respectively. Then each of the sub-divisions is addressed. First those of the visible segment,

"...as an expression of the ratio of their comparative clearness and obscurity you will have, as one of the sections of the visible world, images. By images I mean, first, shadows, and then reflections in water and on surfaces of dense, smooth and bright texture, and everything of that kind..."

“As the second section assume that of which this is a likeness or an image, that is, the animals about us and all plants and the whole class of objects made by man.”

So we have images and artifacts as our visible foundation. There is the table as artifact I can rest food or my feet on, and the image of the table in the reflection of a mirror or composed in paint on a canvas. There is not an actual table in the artifact-parts of paint, canvas and frame, yet the image is capable of conveying "table" nonetheless.

The non-visible and intelligible segments breakdown comes next. Glaucon finds Socrates' explanation less than illuminating and requests a re-explanation.

Socrates: “Consider then again the way in which we are to make the division of the intelligible section.”

Glaucon: “In what way?”

Socrates: “By the distinction that there is one section of it which the soul is compelled to investigate by treating as images the things imitated in the former division, and by means of assumptions from which it proceeds not up to a first principle but down to a conclusion, while there is another section in which it advances from its assumption to a beginning or principle that transcends assumption, and in which it makes no use of the images employed by the other section, relying on ideas only and progressing systematically through ideas.”

Glaucon: “I don't fully understand what you mean by this,” he said.

Socrates pulls out all the stops and hits poor Glaucon with an answer a bit too steeped in self reference and relation to have been intelligible without several repetitions. His words are accurate however and their meaning will be integral in our quest for quenching desire soon. In the mean time Socrates has a new way to convey his ideas.

The first sub-segment of the intelligible segment is that of hypothesis, mathematical images, and thought. It is that which was previously described to be that "which the soul is compelled to investigate by treating as images the things imitated in the former division, and by means of assumptions from which it proceeds ... down to a conclusion." Here resides, Socrates explains, a system of logical assumptions that can be carefully carried to more cohesive conclusions. Practitioners of this method, he goes on to explain,

"Make use of the visible forms and talk about them... pursuing their inquiry for the sake of the square as such and the diagonal as such, and not for the sake of the image of it which they draw... The very things which they mould and draw, which have shadows and images of themselves in water, these things they treat in their turn as only images, but what they really seek is to get sight of those realities which can be seen only by the mind"

You can draw an equilateral triangle on a chalkboard to aid in understanding a Euclidean proof, but your attitude toward the artifact of the chalk on the board is as if it were but a reflection of the mathematical object existing in this first segment of the non-visible world.

The second sub-segment is perhaps the most difficult to grasp. It is that section which advances from assumption to beginning, that transcends assumption, and in which it makes no use of the images employed by the other section. This system is described as, "Relying on forms only and progressing systematically through forms, it ends in forms too." Socrates says this section is accessible only through the power of dialectic and reason. These hypotheses are not really hypotheses but "stepping stones and springboards" to reach truth, free of hypothesis, pertaining to the starting point of all.

After Glaucon reiterates his understanding Socrates has a final summation of the concept,

"These four sections, assume these four affections occurring in the soul: intellection or reason for the highest, understanding or thought for the second; assign belief or trust to the third, and to the last imagination, and arrange them in a proportion, considering that they participate in clearness and precision in the same degree as their objects partake of truth and reality.”

Now that we have a clear clasp on the complexities of this quadrilateral human condition we can continue.

So what do we desire? We desire those three animal needs of sleep, sustenance, and sex for survival of the species. The last of those though strikes me as somehow separate. While the food and sleep maintain our bodies in our lifetime, the goal of species survival is aimed much higher. It points to a desire for life not just prolonged but also extended beyond bodily death.

In Plato's Symposium Socrates offers a speech at a drinking party to reveal the nature of the love deity Eros, typically associated with erotic love, an entity whose qualities may aid our understanding of the motivation behind the desire to birth children. His story comes in a recounting of a discussion he had with a very wise woman named Diotima who was an expert on the topic.

Eros is said to be love of something rather than nothing, to desire what is not available to him, and to not already have his desire in his possession. Socrates' dialectical companion prior to the start of his story had suggested that Eros was love of beauty, and Eros was far earlier agreed to be a god. Socrates thus makes note of an inconsistency. If Eros is a god who loves beauty he would deny his existence as a beauty possessing entity, based on our fuller understanding of love, as to desire he cannot possess. He is labeled a spirit then, something between gods and man, and is said to facilitate communication between the divine and the decaying. "Occupying the middle position he plays a vital role in holding the world together."

Diotima says Eros' parents were poverty and resource, and is resultantly trapped in a flux between extremes. The first half of the day he'll spend full of vitality and life the next at the brink of death, never wholly destitute or affluent, and most importantly trapped between wisdom and folly as a lover of wisdom.

His status as a lover of beauty is readdressed in search of motive. Why would anyone want to possess beauty? For that matter why would anyone want to possess goodness? Socrates and Diotima agree that love of the good and happiness, and as follows desire to possess happiness and goodness, are qualities common to all humans. Love has taken on many different forms in any occasion where goodness or happiness is the goal. The composer of music desires to make good music and desires to possess both the composition and the happy feelings associated with creation and the pleasure of listening to beautiful music. He is thus a lover of music.

Diotima drops a bomb and explains the desire is not just for simple possession of goodness temporarily but to possess it forever. The application of love in active action is reproduction, physical or mental. An element of the divine is present here as well. Beauty, a characteristic fully present in any deity, provides the urge for reproduction to occur as it excites and attracts, while ugliness in contrast offends and causes the passion for procreation to pass. The possibility that love is desire of beauty is finally dropped in favor of the desire to use beauty to beget and bear offspring. Diotima address' animal's desire to reproduce as evidence that all things that are mortal desire to be immortal. Unfortunately we are trapped in a form that is always changing. It is not the case that any creature remains precisely the same in every detail, only the divine have this quality. The inner workings of our mind are constantly shifting as we change moods or dispositions in the short term, and forget knowledge as other knowledge replaces it on a longer scale of time. It is through creation that we glimpse immortality. Thus parents will starve so their offspring survive as they can see a part of themselves living on in this way.

Having fully addressed the physical reproduction of offspring she shifts her focus to another means of grasping for immortality. She reminds Socrates of human ambition driving men to do such extraordinary acts that they earned immortality in the memory of their people and many people to come.

"Do you suppose,’ she asked, ‘that Alcestis would have died for Admetus, or Achilles have sought death on the corpse of Patroclus, or your own Codrus have welcomed it to save the children of his queen, if they had not expected to win “a deathless memory for valor,” which now we keep? Of course not."

Most anyone who seeks their immortality in the physical will not go this most glorious of routes and opt simply for child rearing.

In another kind of person there is a desire to be creative mentally. They produce thoughts instead of babies. Diotima suggest all poets and artists belong to this category, as do those involved in the political sphere and anyone concerned with justice or judgment. A man who has this drive to produce with the mind will at an early age be attracted to one person possessing beauty. He'll embark on long conversations in attempts to produce with this beautiful companion an idea worthy of immortal preservation. Soon his appreciation for beauty will expand and he'll understand the physical beauty of one to be akin to that of another. If he is pursuing physical beauty it would be immature not to acknowledge the beauty present in all bodies as one. This should allow him to withdraw a little from his single pursuit and come to recognize the elements of beauty, first, in a second individual, and eventually in all things in the physical world. She continues,

"The next stage is to put a higher value on mental than on physical beauty. The right qualities of mind, even in the absence of any great physical beauty will be enough to awaken his love and affection. The aim is that as the next step he should be compelled to contemplate the beauty of customs and institutions, to see that all beauty of this sort is related, and consequently to regard physical beauty as trivial."

This new man stares out on a limitless ocean of beauty and is enamored with philosophy. He produces many fine arguments and thoughts until he stumbles upon a certain piece of knowledge. This knowledge is knowledge of a beauty which Diotima describes at length as being "the final end and goal of this education," it is eternal, and exists by itself and with itself unique. All other forms of beauty are said to arise from this thing.

Diotima labels this entire process a ladder of love. You climb it progressing from love of one person, to two, to a love of all physical beauty, to a love of beauty in human behavior, then to broad subjects of study, finally ending at that branch of knowledge which only studies ultimate beauty. By producing and caring for the real goodness derivative of that ultimate beauty, she suggests we befriend the gods, and that makes us immortal.

"Men in this condition enjoy a far fuller community with each other than that which comes with children, and a far surer friendship, since the children of their union are fairer and more deathless. Every one would choose to have got children such as these rather than the human sort-- merely from turning a glance upon Homer and Hesiod and all the other good poets, and envying the fine offspring they leave behind to procure them a glory immortally renewed in the memory of men. Or only look,’ she said, ‘at the fine children whom Lycurgus left behind him in Lacedaemon to deliver his country and--I may almost say--the whole of Greece; while Solon is highly esteemed among you for begetting his laws."

At this point the answer to our opening question may at last be in sight. If Diotima persuades us, then the greatest of desires is immortality. It can be attained through several means. Let us first address that which transpires in the visible. There is the immortality to be attained from love of glory through action. If one can achieve great enough a task or die in a certain magnificent and tragic or heroic enough manner, his story may be passed down throughout the ages. This seems to possess very little possibility for success. Not only must you commit an act of incredible virtue, but you must reside forever after as an image of yourself in story. For there is no element of your physical form present, and you have conceived of nothing but a fleeting memory of a chance event. The tale becomes like a shadow of the event and it would be very easy for it to become distorted or false and no longer represent you at all. This might be called immortality of the imagination, and be found situated in the bottom of the divided line in the segment of images and imagination.

We catch some fragment of immortality when we experience Eros to beget children in the physical world, as a part of ourselves is thus placed in a position where it can outlive our immediate life and go on to beget again. This form of love resides in the world of trust and physical things on the divided line. It is a physical love that places the bodily functions in motion for the birthing of a child. The certainty of immortality from this avenue is fleeting, yet more certain than the previous segment. There is no way of knowing your children will have children or that those children will beget again. What you envision as a timeless lineage being established might blink out any time after the first generation. The conception of children is so widespread and naturally occurring though, that your chances are pretty good your offspring will multiply exponentially into the future.

Now we move to the non-visible domain. As the cuts of the divided line were made, first at unequal distances and then each of those parts split to the same ratio, the center two segments establish a mean proportional. They are of equal length and represent a middle ground between the extremes of images and forms. Let the division be made according to this rule.

(A+B):(C+D)::A:B::C:D

From here alternado (Euclid V.16) (A+B):(C+D)::C:D becomes (A+B):C::(C+D):D

As A:B::C:D by componendo (Euclid V.18) then we can say (A+B):B::(C+D):D

By Euclid V.11 then (A+B):C::(A+B):B

And consequently Euclid V.9 says C=B

You might remember the first definition offered by Socrates of the segment of thought in the divided line. "that there is one section of it which the soul is compelled to investigate by treating as images the things imitated in the former division, and by means of assumptions from which it proceeds not up to a first principle but down to a conclusion." We can see love of immortality through thought here when we consider an artist or a scientist. The same way multiplication of humans could be applied to the multiplication of numbers, you take two unique values and in their combination create a wholly new number, the process can be inverted, and thought can be extrapolated and drawn down to a conclusion that applies to the physical world. If I know I can construct a cube from six squares, I can take this information and construct from six flat square-like panels of stone a cube-like box for living or storage depending on size. I am now an artist of cube construction. If my cubes are in enough possession of good then I may gain renown as a constructer of cubes and be remembered forever. Consider that many inventive and excellent creations are given their creators namesake. Here also the scientist can pose a hypothesis and look for a conclusion, if his supposition is correct enough for application in the physical world his theory can boost him to memory worthy status. The visible world lacks the clarity and precision that we find is entirely present in the pure objects of thought. Their clarity allows us access to some power over elements of the physical world, but they lack a comprehensive understanding of phenomenon, as they never progress from their hypothesis to beginnings, but only conclusions. Arts and sciences demonstrate that the properties of the visible world do indeed follow from something intelligible belonging to a higher level. These properties can be thoroughly immortal and their chance discovery by hypothesis can earn a human immortality. The nature of these discoveries is somewhere between mere opinion and knowledge.

The last segment of the line corresponding to the forms and the process of truth seeking through dialectic can be seen as an original to the thought segment's image-like process of hypothesis. Here questions are posed about thoughts themselves and progressing from supposition to supposition intelligible objects are separated into parts, if they have the ability, or collected into wholes, if the combination is appropriate. This process can both be seen to progress upward toward unified beginnings as well as breaking down to final objects. This investigation does not concern itself with the physical, but this love of the intelligible instead seems something akin to the communing with the highest love that Diotima introduced.

Again, the ladder of love moved us from love of that which resides in the physical, the bottom two segments of the line, to the love of beauty in behavior and subjects of study, the lower section of the intelligible segment, to a love of the branch of knowledge which concerns itself only with ultimate beauty, the true nature of things as revealed through dialectic. Interaction with ultimate beauty allows us to produce ideas exemplifying true beauty like the production of children. The process is akin to erotic conception as it requires more than one human and produces an offspring that based on its rearing and its virtues will survive or die. These ideas can be transplanted into physical forms, the poetry of Homer, the establishment of Athens by Solon, or the philosophical writing of Plato.

So we've discovered a number of routes to the satisfaction of our desire. We can funnel our efforts into the pursuit of immortality through perceived greatness in the eyes of others, through the physical production of children, through the physical application of thought for the pursuit of power, or through a love of beauty that leads to a love of truth a blessing of immortality from the gods. Focusing into one the visible or non-visible worlds for satisfaction now seems silly as the lines have blurred between where your gained immortality actually arises. Diotima's ladder showed that the more we focus our satisfaction of desire to the intelligible, the more our physical desires fade. We cannot deny the visible world however, because the animal process of physical reproduction will always be a necessity for the continuation of life.

The sections of the divided line should "participate in clearness and precision in the same degree as their objects partake of truth and reality." The objects in possession of the most truth are those closest the beginning, rather than that which ignores the need for a beginning. Physical objects lack clarity and precision as well as providing only fleeting satisfaction. As the minds memory fades and is replaced by new knowledge, so too do satiations of our sensual appetites inevitably fade replaced by new objects of fancy.

So I offer an impasse between visible or intelligible in absolute. We must side with the Great Spirit Eros. His manifest passion in the physical leads us to multiply and continue as a human whole, while his position as a lover of wisdom (one who does not possess but desires) straddles that of the Individual human experience in a quest to glimpse ultimate beauty. We are forced to live in the physical world, and its immense possibility for distraction from our goal, by our appetites for simple satisfaction, or our desire to use unfounded hypothesis as a means for the acquisition of power, must be ignored. Socrates uses a mathematical image in the divided line proposition, but his end is not an exact demarcation of the proportions of the segments to any end applicable to material objects. He wants us to use it as a springboard for the further discussion of forms aiming at truth. Eros will help us here too. His instilling in us a love of immortality can bring us beyond the petty and the unfounded to the truth. Eros offers a satisfaction first dealing with the bare necessity and eventually extending far beyond the physical. For the body is fragile, it breaks and wastes away, continents shift and species go extinct, metal rusts, shorelines erode, but ideas are immortal.

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home

Archives

February 2006 March 2006 April 2006 May 2006 June 2006 July 2006 August 2006 September 2006 October 2006 November 2006 December 2006 April 2007 June 2007 July 2007 September 2007 October 2007 November 2007 January 2008 February 2008 March 2008 May 2008 July 2008 August 2008 October 2008 November 2008 January 2009 March 2009 June 2009 August 2009 November 2009 January 2010 February 2010 March 2010 April 2010 June 2010 July 2010 December 2010 January 2011 February 2011 April 2011 June 2011 December 2011 February 2012 May 2012 April 2013 October 2013 September 2014 March 2016 May 2018 November 2019 April 2020

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]